A chance encounter in Paris has transformed into preparations for the upcoming series When The Sirens Fade, dedicated to Ukrainian artists. The project will be directed by 38-year-old Sindbad, the great-grandson of Peggy Guggenheim — a member of the legendary family whose connection to the art world spans generations.

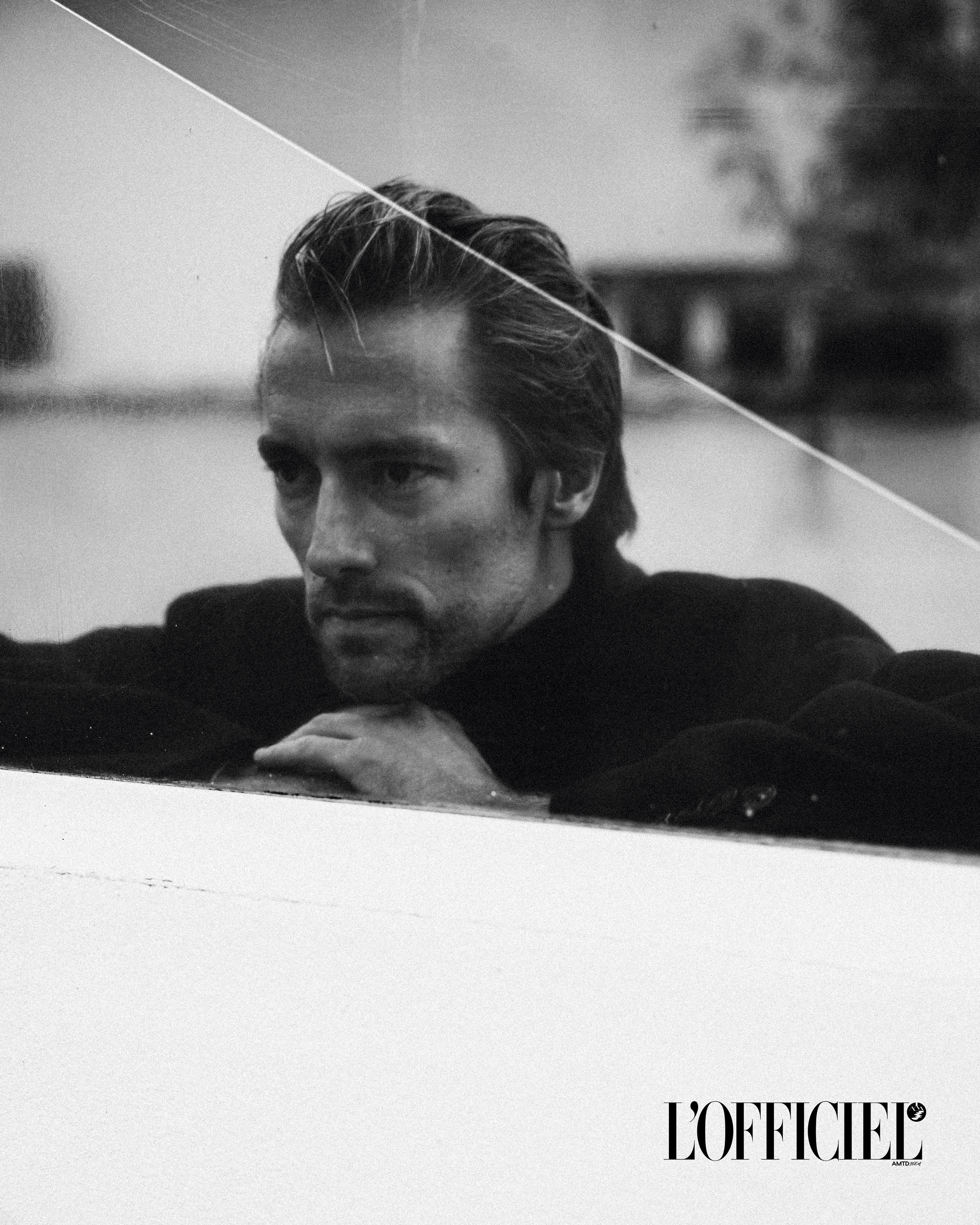

We are all shaped by our childhood, and the protagonist of this autumn issue’s cover story is infused with everything beautiful that has surrounded him throughout his life — the very things he now shares with viewers through photography and film. The following conversation, a two-hour journey from Paris to Galleria Continua in Les Moulins, is yours to discover.

Where you grew up, what and who influenced you, your hobbies?

I grew up in Paris, but my roots run deep into the art world. My father, Sandro, was born and raised in Venice—literally in the palazzo that is now the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. On his side, Peggy Guggenheim was my great-grandmother, so Venice has always felt like a second home. Both of my grandparents were artists, and that shaped my father’s path and, in turn, mine. My mother runs Les Éditions de l’Herne, a small but very prestigious publishing house founded by my grandfather, renowned for its monographic Cahiers—Borges, Gombrowicz, Lévi-Strauss, Arendt, Levinas, Chomsky, among others—and a recent Cahier Picasso.

From a young age I spent countless hours in my father’s gallery—in Paris and in New York—and I followed him everywhere: working alongside him at art fairs, and spending time in artists’ studios and workshops. For generations, my family has told stories with—and through—artists in galleries, books, and museums. Documentary is my way of continuing that tradition—collaborating closely with people so lived experience becomes cinema. I also traveled widely—Mexico, Peru, Cuba—always with the instruction to dive into local culture. Over time, culture became a language for me: the way I understand the world and connect to people. Outside of work I’m happiest doing more of the same—films, cooking for friends, listening to records on a good hi-fi, and getting out into nature to reset.

My father later opened a gallery called Art of the Century, named after Peggy’s pioneering New York space, Art of This Century (57th Street, 1942). Designed with architect Frederick Kiesler, it offered four immersive rooms (Abstract, Surrealist, Kinetic, Daylight) that bridged the European avant-garde and a rising American scene—launching Jackson Pollock’s first solo show (1943), championing Motherwell, Baziotes, Rothko, Clyfford Still, Pousette-Dart, and staging the trailblazing “Exhibition by 31 Women” (1943) with Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, Lee Krasner, Meret Oppenheim, Louise Nevelson, and others.

How did you get into documentary filmmaking?

I came to documentary through the art world. Early on I worked with my father, traveling to art fairs and being immersed in visual culture. That’s when I picked up a camera and fell in love with telling stories through a frame. Later, in New York, I discovered a more cinematic approach to nonfiction and spent time at festivals like Sundance. I realized documentary could blend craft, empathy, and impact. My aim isn’t to lecture; it’s to inspire and leave an emotional imprint that lingers after the credits.

How do you choose topics for your narratives?

Often, the topics choose me. I’m drawn to stories where private lives intersect with larger historical forces—where intimacy and scale coexist. My first long project followed Central American migrants; listening every day confronted me with my own privileges and clarified how to use them in service of others’ stories.

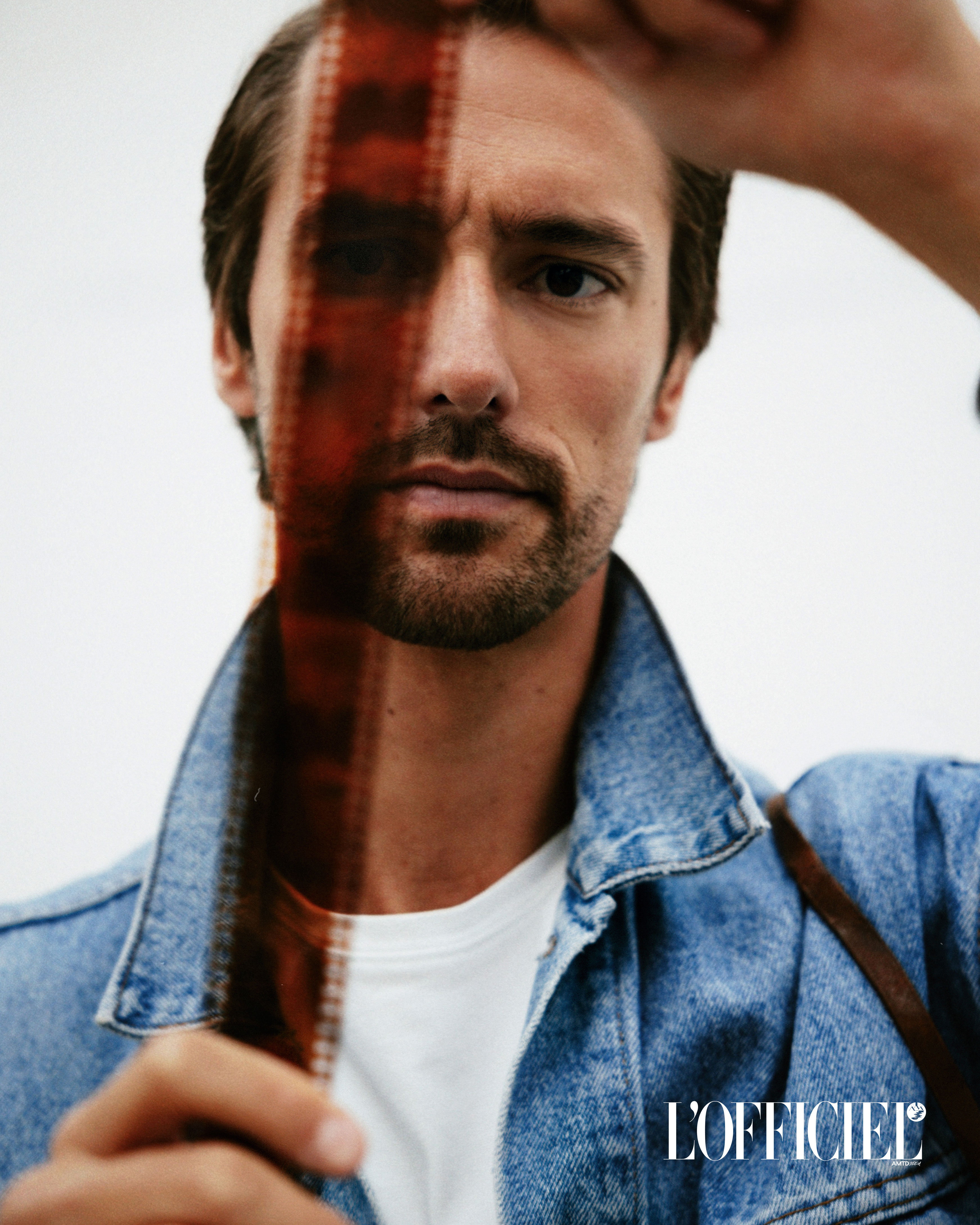

Pascale Marthine Tayou, Tch âm, exhibition views – Galleria CONTINUA, Les Moulins (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025. Details: Pascale Marthine Tayou, Coton tige, 2015.Denim jacket, jeans, LEVI’S. T-shirt, OCTOBRE ÉDITIONS x AMANDINE PANDA. Belt, RALPH LAUREN RRL Coat, IRO. Boots, FRYE

When I began thinking about Ukraine, my background meant I naturally looked at artists first. But as I listened and met more people, it became clear that culture is an ecosystem, and each practice is its own language exploring different themes. Architecture asks how to rebuild well in wartime—think of Balbek Bureau’s RE:Ukraine modular housing and dignified layouts. Music reimagines rhythm under curfew—DJs and festivals shifting to daytime. Visual art turns matter into memory—Zhanna Kadyrova’s Palianytsia stone “loaves.” Food keeps continuity and care—Mirali’s fiercely seasonal kitchen in Kyiv. Expanding to the wider creative community gives a truer, more generous portrait of Ukrainian identity right now.

How did the idea to make a film about Ukrainians come about?

It grew out of admiration and proximity. I was meeting Ukrainian artists and creatives who had relocated to Paris; their stories were full of courage, humor, hospitality, and longing. From there I was drawn to those who chose to remain in Ukraine—people making work in the midst of sirens and uncertainty.

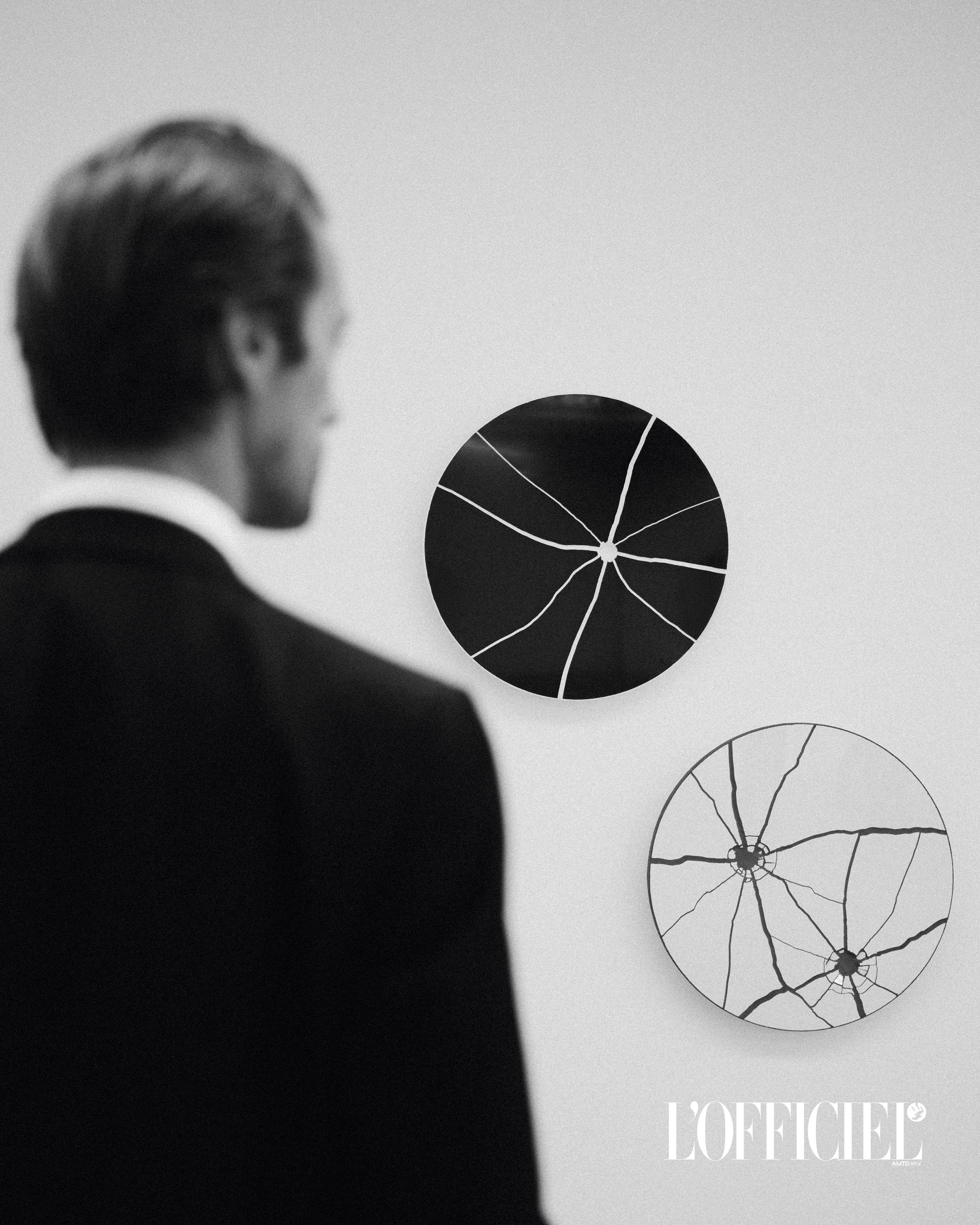

One of the first works that made the war feel close to me was seeing Zhanna Kadyrova with Galleria Continua. I’ve always loved this gallery—they don’t behave like a conventional white cube; their programming is alive, with happenings that keep the conversation moving. I was struck by shows like Palianytsia in Paris and, more recently, Strategic Locations—and by the way her works are also on view at Les Moulins, their vast site just outside Paris. That former paper mill is rough and industrial, and it changes how the work reads—material, scale, and context speak louder there. I’m happy they represent and support Zhanna; that encounter helped set the tone for my project: meet culture where it is, and document it as it lives.

Wool suit, LANVIN. Tank top, BURBERRY. Sneakers, CONVERSE. José Yaque, Interior con Huracиn, 2024. Exhibition views Galleria CONTINUA Les Moulins. ADAGP Paris, 20

Who among Ukraine’s creatives has inspired you?

A spectrum of voices across disciplines—each practice a different lens on identity. Balbek Bureau thinks about how to rebuild, and with what, designing modular housing that preserves dignity. The electronic scene re-imagines nightlife as daylight gatherings to honor curfew and community. Zhanna Kadyrova turns river stone into “bread” to raise funds and remember. Mirali keeps hospitality alive through a fiercely seasonal kitchen in Kyiv. Alongside them: Onuka, DJ Nastia, Sasha (Oleksandr) Rudynskyi, Oleksii Bazela, Sestry Feldman, Shchukariba, Ruslan Baginskiy, Masha Reva—together forming a chorus rather than a solo. They bring energy, welcome, and hope—proof that resilience can look like a studio light turning on, a rehearsal starting on time, a table laid for friends.

How do you work on your films?

My practice is rooted in cinéma vérité / direct cinema—small, agile setups and long, patient relationships so the camera can become invisible. It’s a fly-on-the-wall immersion that lets audiences step inside someone else’s experience.

A major influence is Kirsten Johnson. Her films Cameraperson and Dick Johnson Is Dead investigate identity and relationships in ways that profoundly shaped me. Early on, she generously joined me for a three-day shoot in Iowa around a monumental Jackson Pollock mural commissioned by my great-grandmother in the 1940s and later gifted to an Iowa institution. On that shoot she operated camera with me, modeled how to let scenes breathe, and later offered thoughtful notes. That mentorship reinforced a human-first, patient way of filming that I carry into this project—especially as it relates to Ukrainian identity and how creatives are preserving and reshaping it during the war.

What are your interests and range of hobbies?

Most of my interests orbit culture. I often travel for exhibitions and festivals or to support friends’ shows. I’m passionate about cinema—watching as much as making—and I love the tactile ritual of listening to music on a proper hi-fi. Cooking and time in nature help me reset; they’re as essential to my process as any lens.

What does war mean to you—especially in the context of this project?

Denim jacket, LEVI’S. T-shirt, OCTOBRE ÉDITIONS x AMANDINE PANDA

War interrupts time; everyday life pauses and meaning becomes urgent. Every conflict is unique, and the war in Ukraine must be acknowledged on its own terms. Experiences with other communities have broadened my understanding of human struggle, but I’m not equating those with the reality of war in Ukraine. I try to tell these stories with respect and gravity—attentive to the devastation people face and to the quiet forms of care that persist alongside it.

What stage is When the Sirens Fade at right now?

We’re in development moving into early production. Our access with several artists is confirmed, and we’re sequencing filming windows around the real pace of their lives while finalizing financing. The structure is there, but the work remains flexible—so the film can listen as much as it shows.

Are you planning to film in Ukraine?

Yes—in the near term. The project only makes sense if we’re there, shoulder to shoulder, while the culture is being made.

Who will you work with on the ground?

An all-Ukrainian team—on set and in post. I’m not bringing a foreign crew. I’ll direct (often operate camera), and we’ll staff the production in Ukraine: line producer/production coordinator, fixer-translator, camera, sound, gaffer, production assistants, and a safety advisor. In post we’ll prioritize Ukrainian editors, colorists, composers, and designers so the voice stays rooted locally.

Coat, IRO

Are you exploring co-production with Ukrainian companies?

Absolutely. I’m particularly interested in Tabor, a Ukrainian production company whose recent three-part series Militantropos reached Cannes to strong reception. We’re discussing how to partner in a way that protects access and safety while keeping the authorship authentically Ukrainian.

How do you approach safety and ethics while filming during war?

With humility and clear boundaries. We work with trauma-informed practices, treat consent as ongoing, and never ask anyone to do something that could jeopardize them. We keep risk thresholds for travel and filming; when the context changes, we pause. The camera should center dignity, not just collect images.

Coat, IRO

What do you want partners and audiences to take from the project?

Connection—and a sense of welcome. I want viewers to feel close to people they might never meet, and to recognize Ukraine through its studios, kitchens, rehearsal rooms, and gatherings—not only through headlines. For partners—cultural institutions, broadcasters, foundations, aligned brands—the invitation is to help this work travel: co-produce, host screenings and conversations, support outreach, and make sure these voices are heard widely.

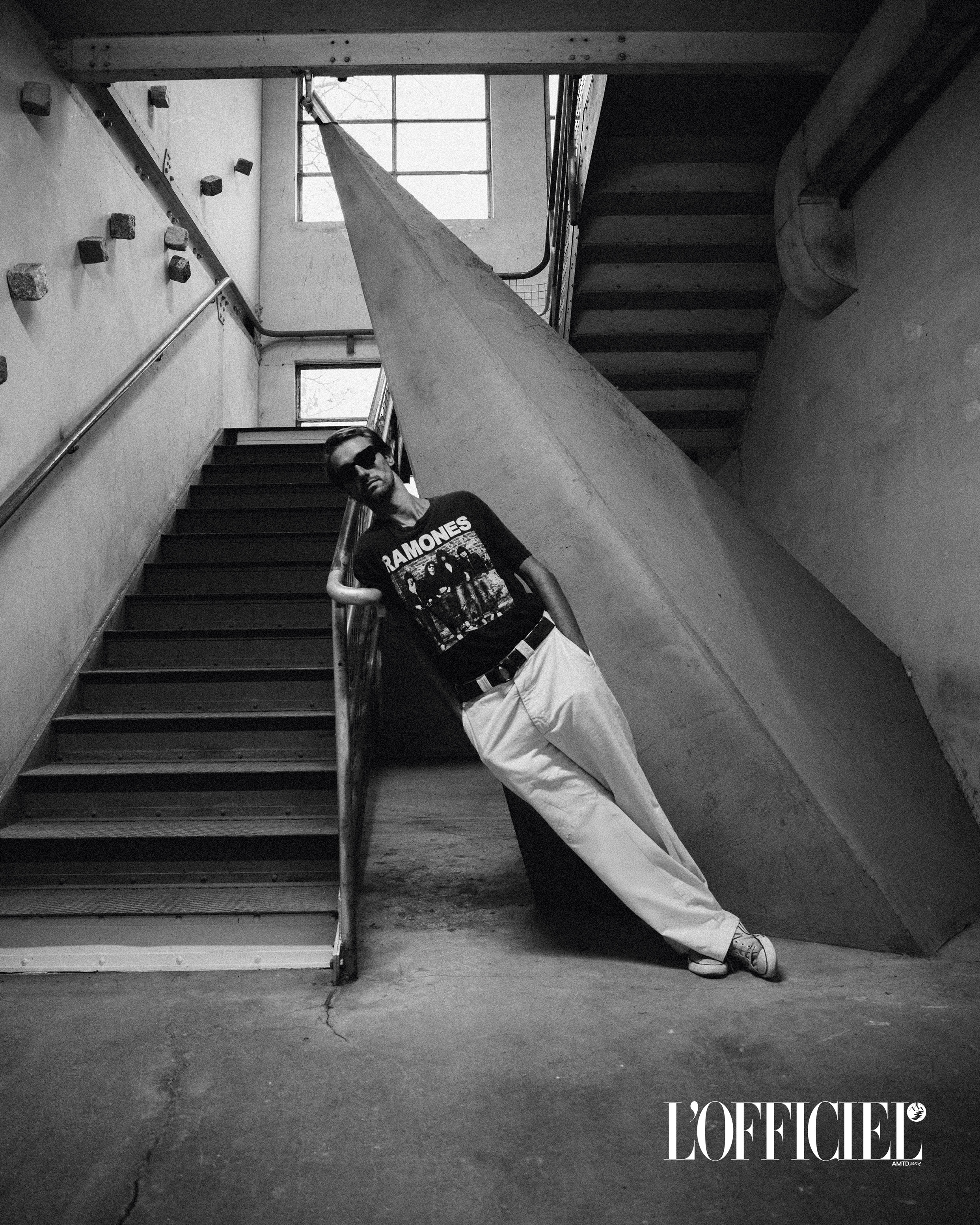

Vintage T-shirt. Pants, belt, RALPH LAUREN RRL. Sneakers, CONVERSE. Sunglasses, LGR. Zhanna Kadyrova, Invisible Forms, 2012

How will people be able to see the work?

We’re building it as a serial project for broadcasters/streamers and cultural venues, alongside a feature-length anthology cut for festivals and museum screenings with conversations and performances. The spirit is intimate and cinematic, so it can live in both worlds.

What higher goals do you pursue with your art?

Impact through empathy. I want to build emotional bridges so audiences can feel close to lives they might never live. In an age of information overload, I lean on a vérité, immersive language because emotion helps us truly care. If a film moves someone to see differently—to reach out, support, protect—then it’s done meaningful work. With When the Sirens Fade, the goal is not only to document, but to connect: to help safeguard culture by amplifying the people who keep it alive.|

Tuxedo, LANVIN. Shirt, ETON. Zhanna Kadyrova, Shots, 2014–2023

The editorial team extends its special gratitude to Galleria Continua, Les Moulins, for providing the location and assisting in the organisation of the shoot. www.galleriacontinua.com

Interview: Aleksey Nilov

Photography: Nick Naida